Read the below article and it got me thinking. What’s interesting is that PET (what bottles are made of) does not float…even if it fragments. The plastics that are swishing around in the Garbage patch are not PET bottles and a lot of people do not realize that. I definitely do not think that just because bottles, or PET sink, that that is not pollution because its still there. But there are SO many other products out there…medicine bottles, laundry bins, storage containers, scissor handles,trash cans,caps, product packaging, etc. why is always the “bottles” that get pointed out? I think its important for people to make changes in their habits/lifestyles to better the earth…but until companies make the decision to do so as well, a lot of us will find it almost impossible to avoid all of the plastic that we accumulate. We need solutions, that will work…no green washing…so companies and consumers can make the right decisions about the earth friendly products they will implement in their lives.

Conservation of mass often applies to college-level physics problems: in a closed system, mass can neither be created nor destroyed. In the case of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch – a gigantic section of the ocean littered with an unusually high amount of man-made trash — the system is clearly not closed. Yet conservation of mass is almost precisely what we see, both in the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans: more than 20 years of waste plastic studies in these oceans have demonstrated that the garbage patches are neither growing in size nor shrinking. They have conserved their mass. While plastic production rates have skyrocketed, as well as human consumption of plastic-contained goods, the plastic masses in these oceanic gyres (very large circular current patterns spanning thousands of miles) are incontrovertibly the same now as they were in the 1980s.

Interesting. If the rate at which plastic enters the patch has increased while the total mass of the patch has remained constant, then there must have been a corresponding increase in the rate at which plastic leaves the patch, to balance. Some scientists have hypothesized that the depths of the oceans act as plastic “sinks” from which waste never returns. If this were true, huge collections of settled ocean plastic debris should be established across the world. But for all their efforts, scientists have not been able to locate such sinks. With no evidence to support the ocean sink hypothesis, researchers have been looking for alternative answers for decades. What they have recently found may surprise you.

In a recent article appearing in Nature News, marine chemist Tracy Mincer and colleagues at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) reported the observation of oceanic bacteria actively consuming bits of plastic recovered from ocean gyres. At a glance, their result are not so shocking. After all, we have long known that microbial communities can (slowly) degrade plastic in landfills, over many years. However, it had been previously thought that the ocean gyres were too nutrient-poor to sustain substantial bacterial colonies. Therefore, the group’s findings help shed light on what has been a rather intriguing puzzle to scientists.

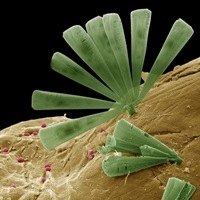

Scanning electron micrograph of the same sheet of plastic shown above reveals millions of plastic-eating bacteria

Of course, all scientists know that by answering one question, hundreds more arise. Most importantly, currently no one knows what chemical compounds microbes degrade plastic into. They could be biologically benign compounds, or they could be toxic. Concentrated breakdown of plastic into toxic compounds in ocean gyre masses, or landfills, could spell eventual disaster for local ecological communities. Through biological magnification, toxins can be stored inside animals’ bodies. As prey is consumed at higher and higher levels up the food web, the largest predators end up with the highest concentrations of toxins – think the bald eagle and DDT. Then multiply the issue by the size of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which is swirling away inside the largest ecosystem on the planet.

Whatever scientists determine about the toxicity of the microbial degradation products of plastic, the rest of the conserved mass of floating plastic will still be there. If we continue our current plastic consumption as societies, then billions of micron-sized particles of human trash will continue to float in our oceans for decades or centuries, just flinking along while fish, whales, and seabirds consume them for dinner. Of course, we can also clearly see that preventative measures would have a profound effect here: if we actively reduce the mass of plastic entering the system while microbial degradation activity remains high, then the total mass of plastic in the oceanic gyres will also decrease. In other words, your actions today directly contribute to the health of our oceans in the future.

I urge you to think about consumption habits that you can change, like carrying a reusable water bottle instead of purchasing bottled water. I never go anywhere without my half-liter Nalgene. Also, you will be happy to know that the I Heart Tap Water campaign is well underway here at UC Berkeley. You can find campus water bottle filling stations on a Google map here.

It’s your choice. You can either let ocean microbes struggle to clean up our oceans for us, or you can actively prevent the contamination of our water with plastic debris by choosing to reduce your plastic consumption and recycling as much as possible.

“Only we humans make waste that Nature can’t digest,” says Moore.

“Only we humans make waste that Nature can’t digest,” says Moore.