Updated by Amy Westervelt on February 13, 2016, 10:00 a.m. ET

Originally published on Ensia.

Criticize recycling and you may as well be using a fume-spewing chainsaw to chop down ancient redwoods, as far as most environmentalists are concerned. But recent research into the environmental costs and benefits and some tough-to-ignore market realities have even the most ardent of recycling fans questioning the current system.

No one is saying that using old things to make new things is intrinsically a bad idea, but consensus is building around the idea that the system used today in the United States, on balance, benefits neither the economy nor the environment.

In general, local governments take responsibility for recycling. The practice can deliver profits to city and county budgets when commodity prices are high for recycled goods, but it turns recycling into an unwanted cost when commodity markets dip. And recycling is not cheap. According to Bucknell University economist Thomas Kinnaman, the energy, labor, and machinery necessary to recycle materials is roughly double the amount needed to simply landfill those materials.

Right now, that equation is being further thrown off by fluctuations in the commodity market. For example, the prices for recycled plastic have dropped dramatically, which has some governments, many of which have been selling their plastic recyclables for the past several years, rethinking their policies around the material now that they may have to pay for it to be recycled. It’s a decision being driven not by waste management goals or environmental concerns, but by economic reasons that could feasibly change in the next couple of years.

Not only that, but in some cases recycling isn’t even what’s best for the environment.

The solution, according to economists, activists, and many in the design community, is to get smarter about both the design and disposal of materials and shift responsibility away from local governments and into the hands of manufacturers.

Material world

Because most people dispose of used aluminum, paper, plastic, and glass in the same way — throw them into a bin and forget about them — it’s easy to think that all recycled materials are created equal. But this couldn’t be further from the truth. Each material has a unique value, determined by the rarity of the virgin resource and the price the recycled material fetches on the commodity market. The recycling process for each also requires a different amount of water and energy and comes with a unique (and sometimes hefty) carbon footprint.

All of this suggests it makes more sense to recycle some materials than others from an economic and environmental standpoint.

A recent study by Kinnaman provides research to back up that assertion. Using Japan as his test case — because the country makes available all of its municipal cost data for recycling — Kinnaman evaluated the cost of recycling each material, the energy and emissions involved in recycling, and various benefits (including simply feeling good about doing something believed to have an environmental or social benefit). He came to the controversial conclusion that an optimal recycling rate in most countries would probably be around 10 percent of goods.

But not just any 10 percent, Kinnaman cautions. To get the most benefit with the least cost, we should be recycling more of some items and less — or even none — of others. “Although the optimal overall recycling rate may be only 10%, the composition of that 10% should contain primarily aluminum, other metals and some forms of paper, notably cardboard and other source[s] of fiber,” he wrote in a follow-up piece in the Conversation. “Optimal recycling rates for these materials may be near 100% while optimal rates of recycling plastic and glass might be zero.”

Kinnaman’s assertions about plastic and glass have to do with the cost and resources required to recycle those materials versus the cost and availability of virgin materials. But he’s not without his critics, particularly on the plastics front, given that he describes the environmental impact of making virgin plastic as “minimal,” a conclusion based more on the emissions and energy required to recycle plastic than the fact that the stuff persists in the environment forever. Still, Kinnaman’s point — that we need to be choosier about what we recycle — has resonated with environmentalists and waste management experts alike.

The commodities conundrum

Cardboard is among the materials for which recycling is most economically and environmentally beneficial.

We may also need to find a way to decouple recycling from the commodities market. What’s happening with plastics right now is a good example of why. In the eastern US, to cite just one example, prices for recycled PET plastic fell from 20 cents a pound in 2014 to less than 10 cents a pound earlier this year, while recycled HDPE prices dipped from just under 40 cents a pound in 2014 to just over 30 cents per pound today.

That’s thanks to a confluence of factors: Oil prices have dropped from US$120 in 2008 to less than US$35 a barrel today; growth in the Chinese recycled goods market dropped from its typical steady, double-digit annual growth to 7 percent in 2015; and the dollar is strong, which makes American recycled materials more expensive than their European or Canadian counterparts.

“The price drop has come at a time when a lot of cities have severe budget constraints anyway, so some communities are beginning to look more skeptically at recycling,” says Jerry Powell, a 46-year veteran of the recycling industry and longtime editor of the recycling industry trade publication Resource Recycling. “But three years ago, when we had record-high prices, they were expanding their recycling efforts.”

Powell adds that changing technologies can also play a role in determining what does or does not make sense from a recycling standpoint. Recycled plastic, for example, was largely used in carpeting 15 years ago, but these days more of it is making its way back into beverage bottles.

“Nestlé has really led the way on this — they knew they needed more recycled material and so they have invested in processing infrastructure and agreed to pay slightly more for recycled plastic,” Powell says. “Fifteen years ago there was zero recycled plastic going toward making new bottles. Now more is going into bottles because the technology has improved, we’re collecting more plastic, and consumers are more aware and are asking for more recycled content.”

If not recycling, then what?

Although recycling may not be an optimal fate for plastics, neither is landfilling. As a result, governments and businesses are looking into options such as reducing use and returning used materials to the source.

That type of “closed loop” thinking is where solutions to today’s recycling woes tend to be focused. Extended producer responsibility, or EPR, laws for packaging would require manufacturers to take back the plastic, cardboard, and form-fitting foam their products come in, ideally with the purpose of recycling and reusing it in future packaging. Such policies essentially assign manufacturers the task of collecting and processing the recyclable packaging materials they produce.

Companies can set up any sort of recycling system they want — they can continue to fund curbside pickup and pay a recycler to process the material, or they can switch to some sort of drop-off method and opt to do the recycling in house — the only stipulation being that they have some sort of a take-back and recycling program in place.

EPR not only lets local governments off the hook for paying for recycling but also effectively divorces recyclable materials from the commodities market: Companies could opt to sell the recycled material they collect and generate, but they would also have another use for the materials (producing more packaging for their own stuff) should the commodities market crash.

Currently, several European countries — including Belgium, Germany, the United Kingdom, and Ireland — have EPR laws, as do Australia and Japan. In Canada, the province of British Columbia has province-wide EPR laws, while Ontario EPR laws cover about 50 percent of disposable goods.

Germany’s EPR laws for packaging have been in place the longest (since 1991) and offer the clearest picture of the impact these laws have on waste management. According to an in-depth case study of Germany’s EPR system conducted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the country’s EPR laws were credited with reducing the total volume of packaging produced in the country by more than 1 million metric tons (1.1 million tons) from 1992 to 1998 alone, representing a per capita reduction of 15 kilograms (33 pounds).

“Significant design changes were made to reduce the amount of material used in packaging,” the report notes. “Container shapes and sizes were altered to reduce volume, and thin-walled films and containers were introduced.”

The overall market showed a noticeable shift away from plastics as well, with a reduction in total volume from 40 to 27 percent. Germany is one of the European Union’s top recyclers, with 62 percent of all packaging being recycled.

Efforts to pass EPR laws for packaging in 2013 in Minnesota, North Carolina, and Rhode Island met with opposition from the consumer packaged goods industry. But according to Matt Prindiville, executive director of the nonprofit Upstream (formerly the Product Policy Institute), which has long led the charge for packaging EPR laws in the US, the current commodities crash in recycling is making EPR more attractive to local governments.

“The conditions for recycling in the US have only gotten worse,” Prindiville says. “Commodity markets have collapsed, and the revenue cities were used to getting to offset the cost of covering recycling have dried up. That’s driving the conditions for EPR.”

The goal with EPR is to balance the needs of all stakeholders, from companies to recyclers to citizens. If implemented correctly, Prindiville says, it should actually benefit companies, not threaten them. “This is not a tax on your products, it’s about figuring out how to get stuff back and do something with it, and you figure out the financing yourself,” he says. “It is a market-based system.”

Burning — and better

Meanwhile, according to a 2012 report from the nonprofit As You Sow foundation, some $11.4 billion worth of valuable PET, aluminum, and other potentially useful packaging materials are being landfilled each year. A more recent report, published this year by the World Economic Forum and Ellen MacArthur Foundation, finds that 95 percent of the value of plastic packaging material alone, worth $80 billion to $120 billion annually, is lost to the economy.

While Kinnaman makes the case that landfilling those materials doesn’t cost as much as once thought, it’s hard not to see those materials as wasted if they’re just sitting in a hole in the ground. Plus, the MacArthur Foundation report points out that plastic packaging generates negative externalities for companies, such as potential reputational and regulatory risks, valued conservatively by the United Nations Environment Programme at $40 billion.

“Given projected growth in consumption, in a business-as-usual scenario, by 2050 oceans are expected to contain more plastics than fish (by weight), and the entire plastics industry will consume 20% of total oil production, and 15% of the annual carbon budget,” the news release accompanying the MacArthur Foundation report states.

That’s precisely why some countries — Sweden, for example — have come back around to the idea of incinerating garbage now that technology has evolved to reduce emissions from incinerators. Thirty-two garbage incinerators in Sweden now produce heat for 810,000 households and electricity for 250,000 homes.

The US plastics industry has been pushing for a similar strategy for dealing with plastic waste — particularly the latest class of thinner, lightweight plastics that don’t fit into existing recycling streams — but critics note that burning plastic still emits toxic chemicals. Instead, Prindiville says he’d like to see the US work toward building a circular economy, as many European countries are trying to do. “Forward-looking CEOs are really drilling down and questioning what is the role of these materials? What’s the role of packaging? And how do we ensure a cradle-to-cradle loop instead of wasting resources?” he says.

Bridgett Luther, founder of the Cradle to Cradle Products Innovation Institute, says that while legislation might help, it’s when companies also see the value in these materials that things will really change.

To that end, some companies have already created their own take-back programs, motivated by innovation and market forces rather than regulation. Luther points to the carpet industry as an example, with companies such as Shaw Floors and Interface routinely taking their carpet back to recycle it into new carpet. In the beverage industry, Coca-Cola made a commitment to use 25 percent recycled plastic in its bottles by 2015, a number it had to downgrade due to high cost and short supply of recycled material. Walmart is in a similar situation, currently struggling to find the supply to meet its goal of using 3 billion pounds (1 billion kilograms) of recycled plastic in packaging by 2020.

“That material is as good as virgin,” Luther says. “There’s a lot of interesting innovation that could happen and could happen very quickly if groups of industry got together and said, ‘We’re going to come up with our own take-back program.’”

The ultimate solution, according to Prindiville, the MacArthur Foundation team, and Luther, is better design of products and packaging further upstream to plan better for end of life and avoid the waste issue altogether. “You can regulate all day long but it’s easier to incentivize,” Luther says. “And much more interesting.”

Read the quoted article here: http://www.vox.com/2016/2/13/10972986/recycling

A final thought, by Danny Clark – President ENSO Plastics:

Its confusing and sometimes funny to think about the efforts we humans go through trying to solve the problems of the world. The solutions usually range from the simple to the extremely complex. What I find amusing is how many so called “professionals” push for the extremely complex and costly solutions that require legislation and subsidies to make work, when in the end many of the simplest solutions work much better.

How long do we continue to debate the issue of how to handle our waste, and how many billions more do we have to spend before the realities of the “recycle everything” religion comes to the fact and science based conclusion that we should be making our materials integrate into the existing waste environments that we have today.

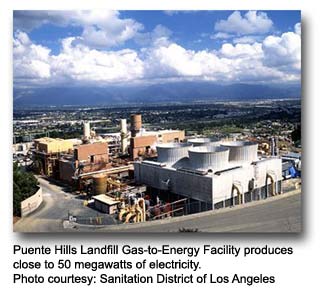

Today, the majority of our trash is already being disposed of into landfills. Over 74% of municipal solid waste is disposed of into landfills that convert landfill gas to green energy. These are already the facts, no need to spend more money, no need to educate, no need to do anything different other than making our plastics fit into these environments.

ENSO RESTORE is a additive that is added into standard plastics to make them landfill biodegradable as well as recyclable. If all plastics were enhanced with ENSO RESTORE we would address nearly 100% of our plastic waste issue. Imagine that for a moment!