IF you live in the United States, you probably do some form of recycling. It’s likely that you separate paper from plastic and glass and metal. You rinse the bottles and cans, and you might put food scraps in a container destined for a composting facility. As you sort everything into the right bins, you probably assume that recycling is helping your community and protecting the environment. But is it? Are you in fact wasting your time?

In 1996, I wrote a long article for The New York Times Magazine arguing that the recycling process as we carried it out was wasteful. I presented plenty of evidence that recycling was costly and ineffectual, but its defenders said that it was unfair to rush to judgment. Noting that the modern recycling movement had really just begun just a few years earlier, they predicted it would flourish as the industry matured and the public learned how to recycle properly.

So, what’s happened since then? While it’s true that the recycling message has reached more people than ever, when it comes to the bottom line, both economically and environmentally, not much has changed at all.

Despite decades of exhortations and mandates, it’s still typically more expensive for municipalities to recycle household waste than to send it to a landfill. Prices for recyclable materials have plummeted because of lower oil prices and reduced demand for them overseas. The slump has forced some recycling companies to shut plants and cancel plans for new technologies. The mood is so gloomy that one industry veteran tried to cheer up her colleagues this summer with an article in a trade journal titled, “Recycling Is Not Dead!”

While politicians set higher and higher goals, the national rate of recycling has stagnated in recent years. Yes, it’s popular in affluent neighborhoods like Park Slope in Brooklyn and in cities like San Francisco, but residents of the Bronx and Houston don’t have the same fervor for sorting garbage in their spare time.

The future for recycling looks even worse. As cities move beyond recycling paper and metals, and into glass, food scraps and assorted plastics, the costs rise sharply while the environmental benefits decline and sometimes vanish. “If you believe recycling is good for the planet and that we need to do more of it, then there’s a crisis to confront,” says David P. Steiner, the chief executive officer of Waste Management, the largest recycler of household trash in the United States. “Trying to turn garbage into gold costs a lot more than expected. We need to ask ourselves: What is the goal here?”

Recycling has been relentlessly promoted as a goal in and of itself: an unalloyed public good and private virtue that is indoctrinated in students from kindergarten through college. As a result, otherwise well-informed and educated people have no idea of the relative costs and benefits.

They probably don’t know, for instance, that to reduce carbon emissions, you’ll accomplish a lot more by sorting paper and aluminum cans than by worrying about yogurt containers and half-eaten slices of pizza. Most people also assume that recycling plastic bottles must be doing lots for the planet. They’ve been encouraged by the Environmental Protection Agency, which assures the public that recycling plastic results in less carbon being released into the atmosphere.

But how much difference does it make? Here’s some perspective: To offset the greenhouse impact of one passenger’s round-trip flight between New York and London, you’d have to recycle roughly 40,000 plastic bottles, assuming you fly coach. If you sit in business- or first-class, where each passenger takes up more space, it could be more like 100,000.

Even those statistics might be misleading. New York and other cities instruct people to rinse the bottles before putting them in the recycling bin, but the E.P.A.’s life-cycle calculation doesn’t take that water into account. That single omission can make a big difference, according to Chris Goodall, the author of “How to Live a Low-Carbon Life.” Mr. Goodall calculates that if you wash plastic in water that was heated by coal-derived electricity, then the net effect of your recycling could be more carbon in the atmosphere.

To many public officials, recycling is a question of morality, not cost-benefit analysis. Mayor Bill de Blasio of New York declared that by 2030 the city would no longer send any garbage to landfills. “This is the way of the future if we’re going to save our earth,” he explained while announcing that New York would join San Francisco, Seattle and other cities in moving toward a “zero waste” policy, which would require an unprecedented level of recycling.

The national rate of recycling rose during the 1990s to 25 percent, meeting the goal set by an E.P.A. official, J. Winston Porter. He advised state officials that no more than about 35 percent of the nation’s trash was worth recycling, but some ignored him and set goals of 50 percent and higher. Most of those goals were never met and the national rate has been stuck around 34 percent in recent years.

“It makes sense to recycle commercial cardboard and some paper, as well as selected metals and plastics,” he says. “But other materials rarely make sense, including food waste and other compostables. The zero-waste goal makes no sense at all — it’s very expensive with almost no real environmental benefit.”

One of the original goals of the recycling movement was to avert a supposed crisis because there was no room left in the nation’s landfills. But that media-inspired fear was never realistic in a country with so much open space. In reporting the 1996 article I found that all the trash generated by Americans for the next 1,000 years would fit on one-tenth of 1 percent of the land available for grazing. And that tiny amount of land wouldn’t be lost forever, because landfills are typically covered with grass and converted to parkland, like the Freshkills Park being created on Staten Island. The United States Open tennis tournament is played on the site of an old landfill — and one that never had the linings and other environmental safeguards required today.

Though most cities shun landfills, they have been welcomed in rural communities that reap large economic benefits (and have plenty of greenery to buffer residents from the sights and smells). Consequently, the great landfill shortage has not arrived, and neither have the shortages of raw materials that were supposed to make recycling profitable.

With the economic rationale gone, advocates for recycling have switched to environmental arguments. Researchers have calculated that there are indeed such benefits to recycling, but not in the way that many people imagine.

Most of these benefits do not come from reducing the need for landfills and incinerators. A modern well-lined landfill in a rural area can have relatively little environmental impact. Decomposing garbage releases methane, a potent greenhouse gas, but landfill operators have started capturing it and using it to generate electricity. Modern incinerators, while politically unpopular in the United States, release so few pollutants that they’ve been widely accepted in the eco-conscious countries of Northern Europe and Japan for generating clean energy.

Moreover, recycling operations have their own environmental costs, like extra trucks on the road and pollution from recycling operations. Composting facilities around the country have inspired complaints about nauseating odors, swarming rats and defecating sea gulls. After New York City started sending food waste to be composted in Delaware, the unhappy neighbors of the composting plant successfully campaigned to shut it down last year.

Sign Up for the Opinion Today Newsletter

THE environmental benefits of recycling come chiefly from reducing the need to manufacture new products — less mining, drilling and logging. But that’s not so appealing to the workers in those industries and to the communities that have accepted the environmental trade-offs that come with those jobs.

Nearly everyone, though, approves of one potential benefit of recycling: reduced emissions of greenhouse gases. Its advocates often cite an estimate by the E.P.A. that recycling municipal solid waste in the United States saves the equivalent of 186 million metric tons of carbon dioxide, comparable to removing the emissions of 39 million cars.

According to the E.P.A.’s estimates, virtually all the greenhouse benefits — more than 90 percent — come from just a few materials: paper, cardboard and metals like the aluminum in soda cans. That’s because recycling one ton of metal or paper saves about three tons of carbon dioxide, a much bigger payoff than the other materials analyzed by the E.P.A. Recycling one ton of plastic saves only slightly more than one ton of carbon dioxide. A ton of food saves a little less than a ton. For glass, you have to recycle three tons in order to get about one ton of greenhouse benefits. Worst of all is yard waste: it takes 20 tons of it to save a single ton of carbon dioxide.

Once you exclude paper products and metals, the total annual savings in the United States from recycling everything else in municipal trash — plastics, glass, food, yard trimmings, textiles, rubber, leather — is only two-tenths of 1 percent of America’s carbon footprint.

As a business, recycling is on the wrong side of two long-term global economic trends. For centuries, the real cost of labor has been increasing while the real cost of raw materials has been declining. That’s why we can afford to buy so much more stuff than our ancestors could. As a labor-intensive activity, recycling is an increasingly expensive way to produce materials that are less and less valuable.

Recyclers have tried to improve the economics by automating the sorting process, but they’ve been frustrated by politicians eager to increase recycling rates by adding new materials of little value. The more types of trash that are recycled, the more difficult it becomes to sort the valuable from the worthless.

In New York City, the net cost of recycling a ton of trash is now $300 more than it would cost to bury the trash instead. That adds up to millions of extra dollars per year — about half the budget of the parks department — that New Yorkers are spending for the privilege of recycling. That money could buy far more valuable benefits, including more significant reductions in greenhouse emissions.

So what is a socially conscious, sensible person to do?

It would be much simpler and more effective to impose the equivalent of a carbon tax on garbage, as Thomas C. Kinnaman has proposed after conducting what is probably the most thorough comparison of the social costs of recycling, landfilling and incineration. Dr. Kinnaman, an economist at Bucknell University, considered everything from environmental damage to the pleasure that some people take in recycling (the “warm glow” that makes them willing to pay extra to do it).

He concludes that the social good would be optimized by subsidizing the recycling of some metals, and by imposing a $15 tax on each ton of trash that goes to the landfill. That tax would offset the environmental costs, chiefly the greenhouse impact, and allow each municipality to make a guilt-free choice based on local economics and its citizens’ wishes. The result, Dr. Kinnaman predicts, would be a lot less recycling than there is today.

Then why do so many public officials keep vowing to do more of it? Special-interest politics is one reason — pressure from green groups — but it’s also because recycling intuitively appeals to many voters: It makes people feel virtuous, especially affluent people who feel guilty about their enormous environmental footprint. It is less an ethical activity than a religious ritual, like the ones performed by Catholics to obtain indulgences for their sins.

Religious rituals don’t need any practical justification for the believers who perform them voluntarily. But many recyclers want more than just the freedom to practice their religion. They want to make these rituals mandatory for everyone else, too, with stiff fines for sinners who don’t sort properly. Seattle has become so aggressive that the city is being sued by residents who maintain that the inspectors rooting through their trash are violating their constitutional right to privacy.

It would take legions of garbage police to enforce a zero-waste society, but true believers insist that’s the future. When Mayor de Blasio promised to eliminate garbage in New York, he said it was “ludicrous” and “outdated” to keep sending garbage to landfills. Recycling, he declared, was the only way for New York to become “a truly sustainable city.”

But cities have been burying garbage for thousands of years, and it’s still the easiest and cheapest solution for trash. The recycling movement is floundering, and its survival depends on continual subsidies, sermons and policing. How can you build a sustainable city with a strategy that can’t even sustain itself?

Read original NY Times article written by John Tierney https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/04/opinion/sunday/the-reign-of-recycling.html?mwrsm=Email

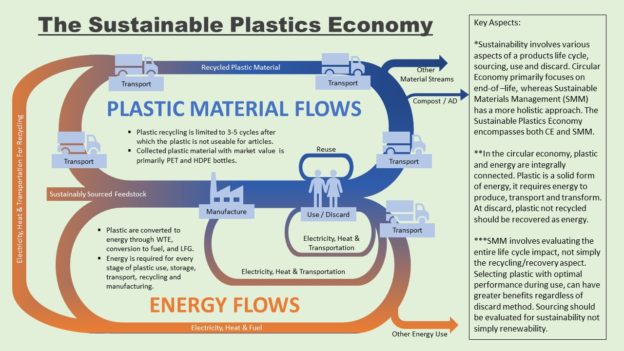

The “root cause” solution to plastic pollution is in making sure plastics work in today’s managed-waste systems. It seems too simplistic an answer considering the enormity of this problem. But when it’s all said and done, plastics (petroleum or plant based) must work in our managed systems, especially the one that primarily collects plastic waste – period. This is the only path to a full life-cycle and systems approach for profoundly better economic and environmental outcomes.

The “root cause” solution to plastic pollution is in making sure plastics work in today’s managed-waste systems. It seems too simplistic an answer considering the enormity of this problem. But when it’s all said and done, plastics (petroleum or plant based) must work in our managed systems, especially the one that primarily collects plastic waste – period. This is the only path to a full life-cycle and systems approach for profoundly better economic and environmental outcomes.

The latest estimates indicate that 8300 million metric tons (Mt) of plastics have been produced to date. As of 2015, approximately 6300 Mt of plastic waste had been generated. Despite the efforts of the last 40 years, only 9% of this material is getting recycled. The environmental impact of plastic pollution is wreaking havoc and if smarter decisions are not made regarding how this material is being managed the effects will certainly be catastrophic for the entire ecosystem.

The latest estimates indicate that 8300 million metric tons (Mt) of plastics have been produced to date. As of 2015, approximately 6300 Mt of plastic waste had been generated. Despite the efforts of the last 40 years, only 9% of this material is getting recycled. The environmental impact of plastic pollution is wreaking havoc and if smarter decisions are not made regarding how this material is being managed the effects will certainly be catastrophic for the entire ecosystem.