Georgia Tech Research News,

9/27/2011

Despite efforts to encourage the recycling of plastic water bottles, milk jugs and similar containers, a majority of the plastic packaging produced each year in the United States ends up in landfills, where it can take thousands of years to degrade. To address that problem with traditional polyethylene, polypropylene, Styrofoam and PET products, researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology are working with the Plastics Environmental Council (PEC) to expand the use of chemical additives that cause such items to biodegrade in landfills.

Analyzing plastics

GTRI researchers Lisa Detter Hoskin and Erin Prowett (seated) use a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer system to test biodegradable polyethylene bags and polystyrene cups to confirm the presence of biodegradable additives. (Click image for high-resolution version. Photo: Gary Meek)

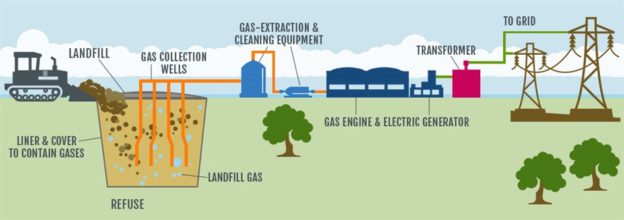

Added during production of the plastic packaging, the compounds encourage anaerobic landfill bacteria and fungi to break down the plastic materials and convert them to biogas methane, carbon dioxide and biogenic carbon – also known as humus. These additives – simple organic substances that build on the known structures of materials that induce polymer biodegradation – don’t affect the performance of the plastics, introduce heavy metals or other toxic chemicals, or prevent the plastics from being recycled in current channels.

If widely used, these additives could help reduce the volume of plastic waste in landfills and permit much of the hydrocarbon resource tied up in the plastic to be captured as methane, which can be burned for heating or to generate electricity.

“Research done so far using standard test methods suggests that the treated plastics could biodegrade completely within five to ten years, depending on landfill conditions,” said Lisa Detter Hoskin, a principal research scientist in the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) and co-chair of the PEC’s technical advisory committee. “However, legislators, regulatory agencies and consumers need more assurance that these containers will perform as expected in actual landfills. We need to provide more information to help the public make informed buying decisions.”

To provide this information, Hoskin and other Georgia Tech researchers are working with the Atlanta-based PEC to develop a set of standards that would ensure accuracy and consistency in the determination and communication of the plastic containers’ biodegradation performance.

“We are working to develop a new standard specification for anaerobically biodegradable conventional plastics,” Hoskin said. “This certification is intended to establish the requirements for accurate labeling of materials and products made from oil-derived plastics as anaerobically biodegradable in municipal landfill facilities. The specification, along with a certifying mark, will allow consumers, government agencies and recyclers to know that the item carrying it is both anaerobically biodegradable and recyclable.”

The standard specification will provide detailed requirements and test performance criteria for products identified as anaerobically biodegradable, and will include rates for anaerobic biodegradation in typical U.S. landfills. These rates will be based on biodegradation test data and results from research being undertaken by Georgia Tech and North Carolina State University.

Analyzing plastics

Researchers Lisa Detter Hoskin (standing, left), Walton Collins (standing, right) and Gautam Patel examine the structure of biodegradable polystyrene cups using a high-resolution optical inspection system. (Click image for high-resolution version. Photo: Gary Meek)

With support from the PEC and its member companies, Hoskin has directed testing efforts that show mechanistically how the additives work, and are showing that the degraded plastic leaves behind no toxic materials. With that part of the project largely completed, she now leads the development of the standard specification and certifying mark, and plans to organize a network of accredited laboratories that will test products made with the biodegradable additives to certify that they do degrade within a specific period of time.

Full development and adoption of the new standard specification by ASTM International will likely take between 18 months and two years, Hoskin said. The project will involve research being done using landfill simulations at North Carolina State University and other independent laboratories.

Using information from laboratory-scale anaerobic reactors operated under a range of temperatures, moisture levels and solids contents, researchers will compare the time required to break down known anaerobically biodegradable materials – such as newsprint, office waste and food waste – against the time required to degrade those same wastes in real landfills. That information will be used to project the biodegradation rate for the treated plastics in a range of real landfills, which vary considerably in moisture and other factors.

Though they are recyclable, plastics made from hydrocarbons had not been biodegradable until development of microbe-triggering additives. Bioplastics such as those made from corn may be composted, while a small percentage of specialized plastic products – known as oxobiodegradables – are designed to degrade when exposed to oxygen and ultraviolet light. But the bulk of the plastic resins used in bottles and other containers are made from materials that will last virtually forever in landfills, noted Charles Lancelot, executive director of the PEC.

Many communities operate recycling programs for plastics and other materials such as newsprint, aluminum and steel cans or cardboard. But because the cost of collecting, sorting, cleaning and reprocessing most plastics can be more than the cost of producing new products, such programs struggle financially unless they are subsidized, he noted.

Plastic bottles

Despite efforts to encourage recycling, a majority of the plastic packaging produced each year in the United States ends up in landfills. Expanding the use of chemical additives that encourage the biodegradation of this packaging could help reduce its impact on landfills. (Click image for high-resolution version. Photo: John Toon)

“If you can make a product like a bread tray and use it over and over again, that is the most efficient alternative,” said Lancelot, who developed successful business-to-business recycling programs while working at Rubbermaid. “But if you can’t reuse it and it’s not cost-effective to recycle it, where is the product going to go? The fact is that despite the best wishes of everybody involved, 75 to 85 percent of the plastics used today end up in landfills. We are addressing that unfortunate reality.”

Although biodegradation occurs to varying extents in all U.S. landfills receiving waste today, many of today’s landfills are optimized for biodegradation, he noted. Moist conditions and recirculation of leachate liquids accelerate the activity of anaerobic bacteria, which will attack plastic materials containing the additives. Such landfills typically do a better job of collecting and beneficially using the methane biogas, Lancelot said.

“When the anaerobic microorganisms that thrive in landfills contact these treated plastics, they begin to colonize on the surface of the plastic and adapt to the base resin,” he explained. “Until the bugs come in contact with the plastic, the additives remain inert and do not affect the properties of the plastic container. We are not changing the overall plastics production process, and the base plastic is the same.”

The compounds, which have been approved by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA), are typically added to the plastic resin in small amounts, between one-half and one percent by weight.

Expanding the use of anaerobically biodegradable additives must be done in such a way that doesn’t detract from recycling programs, said Matthew Realff, a professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Chemical & Biomolecular Engineering and co-chair of the PEC’s technical advisory committee.

“From a lifecycle perspective, it is important to quantify the benefit of recycling over landfill disposal with methane recovery to energy, and to continue to make the case that whenever possible, recycling is significantly better than disposal, even if you have methane production and capture from biodegradation,” he said.

While the biodegradation of plastic materials may solve one problem, the production of methane and carbon dioxide – both atmospheric warming gases – could worsen global climate change, he noted.

“Landfill capture of methane is not 100 percent efficient, nor does it begin immediately after the material is put into the landfill,” Realff said. “Therefore, there will be emissions from biodegradation that will reach the atmosphere. It is important to be aware of how accelerating the production of methane would change overall emissions.”

A 45-year veteran of the U.S. plastics industry, Lancelot says he is pleased to be working with Georgia Tech on a potential solution to the problem of plastics in landfills. The research will help close a gap in plastics “end-of-life” options where reuse or recycling are not feasible.

“Nobody had commercially biodegraded petroleum-based commodity plastics like polyethylene, polypropylene and polystyrene before these additives became available,” he noted. “This is ground-breaking work that is based on a solid scientific platform that defines biodegradability as a practical and useful end result.”

Research News & Publications Office

Georgia Institute of Technology

75 Fifth Street, N.W., Suite 314

Atlanta, Georgia 30308 USA

Media Relations Contacts: Kirk Englehardt (404-407-7280)(kirk.englehardt@gtri.gatech.edu) or John Toon (404-894-6986)(jtoon@gatech.edu).