Guest Blog by Susan Robinson, Senior Public Affairs Director for Waste Management

The other day, two colleagues from the waste and recycling world asked me to help settle a dispute. These two very smart people—one with a Ph.D.—were debating the composition of a plastic microwave tray and how it might be recycled…or not. Should they just toss it in the bin for the recycler to deal with? Municipal guidelines were unclear, but it felt wrong to just throw it in the trash. In the end, they tossed it into the single-stream recycling bin and hoped it would be recycled.

The episode left me wondering. If even we in the waste management world are so confused, what does this mean for the success of recycling in general?

Changing Habits, Changing Waste

Remember newspapers? Once common in American households, newspapers are increasingly a relic, as more and more of us read our news on computers or portable devices. The result? The United States generates a whopping 50 percent less newspaper than we did a decade ago, and 20 percent less paper overall. That’s a huge decrease for a ten-year stretch.

While paper use has declined, the use of plastics has exploded, with new resins and polymers allowing for new possibilities in packaging. Changing demographics—especially the large Baby Boomer and Millennial generations —mean that more consumers are choosing convenient, single-serve packages for meals and snacks.

At the same time, an emphasis on fresh, healthy, and convenient foods is driving a boom in plastic packaging, which can reduce food waste to the tune of preventing 1.7 pounds of food waste for each pound of plastics packaging. However, there is a loss of recyclability on the back end, after those packages have served their use. Today’s recycling materials recovery facilities were built to process approximately 80 percent fiber and 20 percent containers, not the 40/60 or 50/50 mix that we are seeing today. The new mix of inbound material is leading to increased processing costs.

Prevalence of Plastic in Packaging: Saving Grace or Problem Child?

Plastic packaging is both a boon to the environment and a challenge. It’s lightweight, great at protecting and preserving goods, and as a petroleum-based product, in the current global marketplace, it’s cheap. Flexible plastics packaging—also called “pouches”—offer new levels of convenience and freshness, especially in the food industry.

Plastics offer environmental benefits, too. When you look at the entire lifecycle of many types of plastic packaging, they require far fewer raw materials and less energy to manufacture than do other packaging alternatives. Over the years, as the use of plastics has grown in consumer goods and packaging—increasingly crowding out glass, metals, and some paper—society has reaped these benefits. Yet, if there is a downside to plastics, it’s that they have had a dampening effect on recycling quality.

It’s extremely confusing for consumers to understand how to recycle plastics. For starters, there are all the numbers—1 through 7—each with their own, distinct chemical properties, uses, and recyclability. In addition, many manufacturers are including additives to color their packaging, resulting in low-grade plastics that can’t be recycled. So, for every plastic container that can conceivably be recycled—where facilities exist—there are scores that can’t.

So, what do the numbers mean? Here’s a sample consumer plastics recycling guide from Moore Recycling Associates.

Is it any wonder that consumers are confused?

As we all know from experience, it can be mighty challenging indeed to determine how and where to properly recycle these materials. Many of us simply toss plastics into the recycling bin—and hope for the best.

Contamination of the Recycling Stream

The mixing of non-recyclable plastics into the recycling stream—called contamination—is a common occurrence. Types of low-grade plastics are not recyclable, while plastic bags are typically only recyclable by returning them to grocery or retail store for recycling (not curbside), so their presence increases contamination and the cost of recycling across the board. In most communities, an inbound ton of waste now has an average of 17 percent contamination, while some loads can contain as much as 50 percent non-recyclable material.

Lightweighting Adds to the Mix

Lightweighting—using lighter material for a product or reducing the weight of the material itself—is becoming a common practice, especially with water bottles made from PET (polyethylene terephthalate). With lightweighting, a typical water bottle now weighs about 37 percent less than it used to. Lightweighting has many benefits, like reducing the amount of plastics used and therefore produced, and helping to lower freight costs during transport of products. But lightweighting challenges the current economics of recycling.

For example, in the current recycling commodities market, recovered PET plastic feedstock is sold by weight, not volume. This means that we need to process 35,000 more bottles than we used to, in order to create one ton of PET feedstock. Using this formula, we would have to process 3.6 billion more water bottles each year to get the same weight of material that we sold a decade ago. Since our costs are currently based on volume and our revenue based on weight, lightweighting drives up our costs and dampens the long-term economic feasibility of recycling and recovery programs.

The Troubled Economics of Recycling

For the past several decades, our primary customer for many types of recyclables has been China, whose booming economy required an almost constant supply of raw materials. However, as China’s economic growth has slowed, they have started to limit the kinds of recyclable feedstock they will accept, shrinking the marketplace and reducing demand for this material.

At the same time, the strong U.S. dollar makes U.S. recyclables more expensive, and therefore less attractive, on the global market. Low oil prices also make virgin materials more attractive than feedstocks derived from recycled content. In other words, the market for plastic feedstocks is shrinking—just as the costs to create those feedstocks are rising (our next blog will talk more about this).

What Is the End Goal?

As a society, we used to think that if recycling is good, then more recycling is better. We made recycling convenient so we could collect more recyclables and achieve our weight-based goals. In the process of pushing for higher recycling weights, however, many have lost sight of the actual goal: to lessen the overall environmental impacts of the waste we produce. If we go back to this larger picture, we see that success doesn’t necessarily mean recycling large percentages of material based on the weight of the waste stream; rather, success means a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions or raw materials extraction. Recycling is one way to achieve this goal, but it is not the ultimate goal. As we all strive to achieve our overall environmental goals, recycling is just one tool in our toolbox.

The popular, newer, non-recyclable plastics test the very goals of recycling. No one wants to put more plastic in a landfill, but when you look at the true environmental impact of different plastic products and uses, the results might surprise you. For example, an EPA lifecycle study looked at different types of coffee packaging to see which consumed the most energy, emitted the most CO2 equivalent gas, and produced the most municipal solid waste. The researchers found that both the traditional recyclable steel can and the large plastic recyclable container performed worse than the non-recyclable flexible plastic pouch. The lightness and flexibility of the plastic meant such savings in transportation and efficiency that it had a smaller environmental footprint overall than did the recyclable materials.

So, Where Do We Go From Here?

Flexible plastics aren’t going anywhere, so consumer education is crucial to preventing contamination at recycling facilities. This is why recyclers and cities are devoting large amounts of resources to help people understand what’s recyclable—and what’s not. We will eventually figure out how to recycle flexible plastics. However, we also need to rethink what our goals really are—and how best to measure them. Is measuring recycling percentages based on weight the best way? Or is it time to find a new way to gauge our success?

At Waste Management, we believe that it is time to change our collective thinking around this critical issue. As the waste stream is increasingly filled with more energy-efficient and lighter weight materials, it’s simply not sustainable to continue to set recycling goals that are unrealistic and fail to capture important environmental benefits like overall emissions reductions.

Perhaps the time has come to shift to a new metric: a “per capita disposal goal” that can better account for the full value of waste reduction. That’s to say, what if the focus weren’t just how much you recycle, but how much greenhouse gas you avoid? Instead of recycling for the sake of reaching a weight target, the goal would be to achieve the best overall result for the environment.

Such a measure, reflecting a lifecycle approach to managing materials, could go a long way toward accurately capturing the full picture of materials use, and send the right signal for truly sustainable materials management practices.

Additional comments by Danny Clark, President ENSO Plastics

This was a very informative blog by Susan Robinson.

The biggest issue that I see in the industry and with talking to sustainability managers and consultants across the board is that many of them have mistakenly fallen into the trap of going with the “flow” or “public think” about how to implement sustainability for the plastic materials used in products and product packaging. The knee jerk thought that we should recycle everything approach is based more on a feel good response and not on any science or data.

Its only after our first decade into the “green movement” that we are realizing the key to developing solutions that make sense is to use science and data to our approach to determining what will minimize our environmental impact.

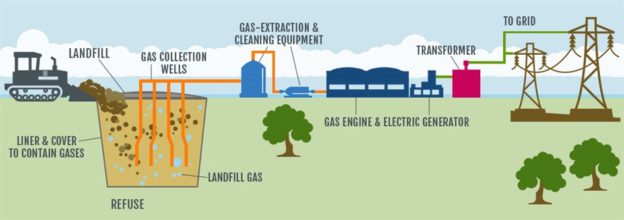

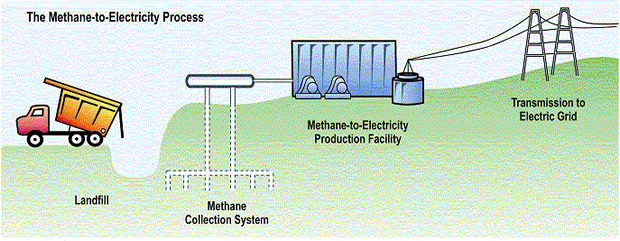

ENSO Plastics is all about the science and data and LCA studies show that we can reduce our carbon footprint with plastics that are designed to be landfill biodegradable. Over 74% of all municipal solid waste is being disposed of into landfills that are already capturing the converting landfill gas to energy. The LCA studies of converting plastics into landfill gas that is then converted to energy reduces the carbon footprint significantly.

As a society we’ve seem to have been pushed into a direction of demonizing landfills while at the same time promoting the notation that recycling everything must be good for the planet. Some of us are just now realizing that the science and data do not support that environmental folklore approach. Its time we get out of our way and rethink the way we address our plastic waste because what we are doing now does not and will not work in the long-run.

Read the original blog here: http://mediaroom.wm.com/recycle-more-or-recycle-better/